What is it?

Pulmonary hypertension is a type of high blood pressure that affects only the arteries in the lungs and the right side of your heart.

Pulmonary hypertension begins when tiny arteries in your lungs, called pulmonary arteries, and capillaries become narrowed, blocked or destroyed. This makes it harder for blood to flow through your lungs, which raises pressure within the arteries in your lungs. As the pressure builds, your heart's lower right chamber (right ventricle) must work harder to pump blood through your lungs, eventually causing your heart muscle to weaken and eventually fail completely.

Pulmonary hypertension is a serious illness that becomes progressively worse and is sometimes fatal. Although pulmonary hypertension isn't curable, treatments are available that can help lessen symptoms and improve your quality of life.

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary hypertension in its early stages may not be noticeable for months or even years. As the disease progresses, symptoms become worse.

Pulmonary hypertension symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea), initially while exercising and eventually while at rest

- Fatigue

- Dizziness or fainting spells (syncope)

- Chest pressure or pain

- Swelling (oedema) in your ankles, legs and eventually in your abdomen (ascites)

- Bluish colour to your lips and skin (cyanosis)

- Racing pulse or heart palpitations

Causes

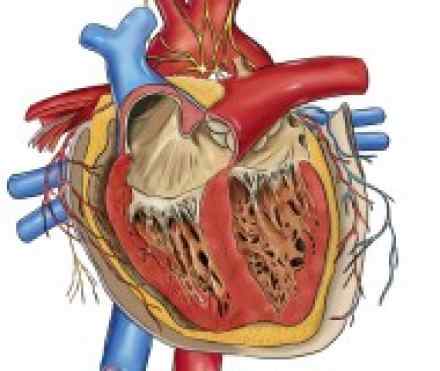

Your heart has two upper and two lower chambers. Each time blood passes through your heart, the lower right chamber (right ventricle) pumps blood to your lungs through a large blood vessel (pulmonary artery). In your lungs, the blood releases carbon dioxide and picks up oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood then flows through blood vessels in your lungs (pulmonary arteries, capillaries and veins) to the left side of your heart.

Ordinarily, the blood flows easily through the vessels in your lungs, so blood pressure is usually much lower in your lungs. With pulmonary hypertension, the rise in blood pressure is caused by changes in the cells that line your pulmonary arteries. These changes cause extra tissue to form, eventually narrowing or completely blocking the blood vessels, making the arteries stiff and narrow. This makes it harder for blood to flow, raising the blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries.

Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension

When an underlying cause for high blood pressure in the lungs can't be found, the condition is called idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (IPH).

Some people with IPH may have a gene that's a risk factor for developing pulmonary hypertension. But in most people with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension, there is no recognized cause of their pulmonary hypertension.

Secondary pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension that's caused by another medical problem is called secondary pulmonary hypertension. This type of pulmonary hypertension is more common than idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. Causes of secondary pulmonary hypertension include:

- Blood clots in the lungs (pulmonary emboli)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, such as emphysema

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma or lupus

- Sleep apnea and other sleep disorders

- Congenital heart disease

- Sickle cell anaemia

- Chronic liver disease (cirrhosis)

- AIDS

- Lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, a condition that causes scarring in the tissue between the lungs' air sacs (interstitium)

- Left-sided heart failure

- Living at altitudes higher than 8,000 feet (2,438 meters)

- Climbing or hiking to altitudes higher than 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) without acclimating first

- Use of certain stimulant drugs, such as cocaine

Risk factors

Although anyone can develop either type of pulmonary hypertension, older adults are more likely to have secondary pulmonary hypertension, and young people are more likely to have idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension is also more common in women than it is in men.

Another risk factor for pulmonary hypertension is a family history of the disease. Some genes could be linked to idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. These genes might cause an overgrowth of cells in the small arteries of your lungs, making them narrower.

If one of your family members develops idiopathic pulmonary hypertension and tests positive for a gene mutation that can cause pulmonary hypertension, your doctor or genetic counselor may recommend that you or your family members be tested for the mutation.

Complications

Pulmonary hypertension can lead to a number of complications, including:

- Right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale). In cor pulmonale, your heart's right ventricle becomes enlarged and has to pump harder than usual to move blood through narrowed or blocked pulmonary arteries. At first, the heart tries to compensate by thickening its walls and expanding the chamber of the right ventricle to increase the amount of blood it can hold. But this thickening and enlarging works only temporarily, and eventually the right ventricle fails from the extra strain.

- Blood clots. Clots help stop bleeding after you've been injured. But sometimes clots form where they're not needed. A number of small clots or just a few large ones dislodge from these veins and travel to the lungs, leading to a form of pulmonary hypertension that is reversible with time and treatment. Having pulmonary hypertension makes it more likely you'll develop clots in the small arteries in your lungs, which is dangerous if you already have narrowed or blocked blood vessels.

- Arrhythmia. Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias) from the upper or lower chambers of the heart are complications of pulmonary hypertension. These can lead to palpitations, dizziness or fainting and can be fatal.

- Bleeding. Pulmonary hypertension can lead to bleeding into the lungs and coughing up blood (haemoptysis). This is another potentially fatal complication.

Diagnosis

Pulmonary hypertension is hard to diagnose early because it's not often detected in a routine physical exam. Even when the disease is more advanced, its signs and symptoms are similar to those of other heart and lung conditions. Your doctor may do one or more tests to rule out other possible reasons for your condition. The first tests you'll have to diagnose pulmonary hypertension include:

- Chest X-ray. This test may be able to check for pulmonary hypertension if your pulmonary arteries or the right ventricle of your heart is enlarged. The X-ray will appear normal in about one-third of people who have pulmonary hypertension.

- Echocardiogram. Your doctor may first suspect you have pulmonary hypertension based on the results of this test. This noninvasive test uses harmless sound waves that allow your doctor to see your heart without making an incision. During the procedure, a small, plastic instrument called a transducer is placed on your chest. It collects reflected sound waves (echoes) from your heart and transmits them to a machine that uses the sound wave patterns to compose images of your beating heart on a monitor. These images show how well your heart is functioning, and recorded pictures allow your doctor to measure the size and thickness of your heart muscle. Sometimes your doctor will recommend an exercise echocardiogram to help determine how well your heart works under stress. In that case, you'll have an echocardiogram before exercising on a stationary bike or treadmill and another test immediately afterward.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram. If it's difficult to get a clear picture of your heart and lungs with a standard echocardiogram, your doctor may recommend a transesophageal echocardiogram. In this procedure, a flexible tube containing a transducer is guided down your throat and into your esophagus using only a numbing spray in the back of your throat. From here, the transducer can get detailed images of your heart.

- Right heart catheterization. After you've had an echocardiogram, if your doctor thinks you have pulmonary hypertension, you'll likely have a right heart catheterization. This test is often the most reliable way of diagnosing pulmonary hypertension. During the procedure, a cardiologist places a thin, flexible tube (catheter) into a vein in your neck or groin. The catheter is then threaded into your right ventricle and pulmonary artery. Right heart catheterization allows your doctor to directly measure the pressure in the main pulmonary arteries and right ventricle. It's also used to see what effect different medications may have on your pulmonary hypertension. Right heart catheterization is usually performed under local anesthesia and sedation in a hospital setting, but you often can go home soon after the procedure. You'll need someone to drive you home after the test.

Your doctor may order additional tests to check the condition of your lungs and pulmonary arteries, including:

- Pulmonary function test. This noninvasive test measures how much air your lungs can hold, and the airflow in and out of your lungs. During the test, you'll blow into a simple instrument called a spirometer.

- Perfusion lung scan. This test uses small amounts of radioactive substances (radioisotopes) to study blood flow (perfusion) in your lungs. The radioisotopes are injected into a vein in your arm. Immediately afterward, a special camera (gamma camera) takes pictures of blood flow in your lungs' blood vessels. A lung scan is then used to determine whether blood clots are causing symptoms of pulmonary hypertension. A perfusion lung scan is usually performed with another test, known as a ventilation scan. In this test, you inhale a small amount of radioactive substance while a gamma camera records the movement of air into your lungs. The two-test combination is known as a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan allows your doctor to see your organs in two-dimensional "slices." In this test, you'll lie in a machine that takes images of your lungs so that your doctors can see a cross-section of them. You might also be given a medication that makes the images of your lungs show up more clearly.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test, which uses no X-rays, is sometimes used to get images of the blood vessels in your lungs. A computer creates tissue "slices" from data generated by a powerful magnetic field and radio waves. An MRI can't, however, measure artery pressure — a procedure that's necessary to check the effectiveness of any medications you're taking to control IPH.

- Open-lung biopsy. In rare situations your doctor may recommend an open-lung biopsy. An open-lung biopsy is a type of surgery in which a small sample of tissue is removed from your lungs under general anesthesia to check for a possible secondary cause of pulmonary hypertension. It would be done only to see if certain treatments might be effective for you, or to allow you to discontinue some medications.

Genetic tests

If a family member has had pulmonary hypertension, your doctor may screen you for genes that are linked with pulmonary hypertension. If you test positive, your doctor may recommend that other family members be screened for the same genetic mutation.

Pulmonary hypertension classifications

Once you've been diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, your doctor may classify the disease using guidelines developed by the New York Heart Association.

- Class I. Although you've been diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, you have no symptoms.

- Class II. You don't have symptoms at rest, but you experience fatigue, shortness of breath or chest pain with normal activity.

- Class III. You're comfortable at rest but have symptoms when you're physically active.

- Class IV. You have symptoms even at rest.

References

http://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases_conditions/hic_Pulmonary_Hypertension_Causes_Symptoms_Diagnosis_Treatment

http://www.medicinenet.com/pulmonary_hypertension/article.htm

https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/az/P/Pulmonary-hypertension/Causes-of-pulmonary-hypertension-.html

http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/pulmonary-hypertension/Pages/causes.aspx