What is it?

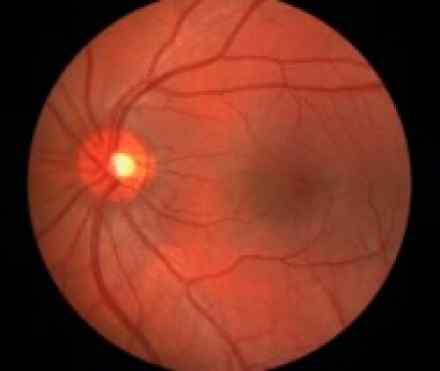

Age-related macular degeneration is a chronic eye disease in which the part of your eye responsible for central vision — your macula— gradually deteriorates, causing blurred central vision or a blind spot in the center of your visual field. Macular degeneration tends to affect adults age 50 and older.

Wet macular degeneration occurs when new blood vessels grow and leak fluid underneath the macula, an area of densely packed light-sensitive cells in the central part of the retina. Most cases of wet macular degeneration develop from the dry type of macular degeneration.

Early detection and treatment of wet macular degeneration may help reduce the extent of vision loss and in some instances improve vision.

Symptoms

With wet macular degeneration, the following signs and symptoms may appear and progress rapidly:

- Visual distortions, such as straight lines appearing wavy or crooked, a doorway or street sign looking lopsided, or objects appearing smaller or farther away than they really are

- Decreased central vision

- Decreased intensity or brightness of colours

- Well-defined blurry spot or blind spot in your field of vision

- Abrupt onset

- Rapid worsening

- Seeing nonexistent things (hallucinating), such as unusual patterns, geometric figures, animals or even faeces, caused by disrupted communication between the deteriorated macula and the brain

Your vision may falter in one eye, while the other remains fine for years. You may not notice any changes or only mild changes because your good eye compensates for the eye with macular degeneration. Your vision and lifestyle are dramatically affected when this condition develops in both eyes.

Causes

Wet macular degeneration develops when abnormal new blood vessels grow from the choroid — the layer of blood vessels sandwiched between the retina and the outer, firm coat of the eye called the sclera — under and into the macular portion of the retina (a process known as choroidal neovascularization). These abnormal vessels leak fluid or blood, which is why this form of macular degeneration is called "wet." Fluid or blood between the choroid and macula interferes with the retina's function and causes your central vision to blur. In addition, what you see when you look straight ahead becomes wavy or crooked, and blank spots block out part of your field of vision.

Eyes with the wet form of macular degeneration almost always show signs of the dry form — yellow fat-like deposits (drusen) and mottled pigmentation of the retina.

The wet form accounts for about 15 percent of all cases, but it's responsible for most of the severe vision loss that people with macular degeneration experience. If you develop wet macular degeneration in one eye, your odds of getting it in the other eye increase greatly.

Much like the dry form of macular degeneration, the wet form may be caused by a breakdown in the eye's waste-removal system. The light-sensitive cells in the retina called cones and rods produce waste. If this waste accumulates, it interrupts the retina's nutrient supply, and retinal tissue deteriorates. Whether this is the mechanism that triggers the growth of abnormal blood vessels is unclear, and it remains the subject of scientific study.

With the wet form of macular degeneration, sight loss is usually severe and rapid, often deteriorating to 20/200 vision or worse, occurring within weeks or months. When vision is 20/200 or worse in both eyes, you're considered legally blind.

Retinal pigment epithelial detachment

Another form of wet macular degeneration, called retinal pigment epithelial detachment, occurs when fluid leaks from the choroid and collects between the choroid and the next-deeper cell layer, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). No abnormal choroidal blood vessel growth is apparent when the RPE is detached. Instead, fluid beneath the RPE causes what looks like a blister or a bump under the macula.

Although this kind of macular degeneration causes symptoms similar to those of typical wet macular degeneration, your vision can remain relatively stable for many months or even years before it deteriorates. Eventually, however, RPE detachment tends to evolve to the more common wet form of macular degeneration associated with the development of newly growing abnormal choroidal blood vessels.

Risk factors

Researchers don't know the exact causes of macular degeneration, but they have identified some contributing factors, including:

- Age. In the United States, macular degeneration is the leading cause of severe vision loss in people age 60 and older.

- Family history of macular degeneration. If someone in your family had macular degeneration, your odds of developing macular degeneration are higher. In recent years, researchers have identified some of the genes associated with macular degeneration. In the future, genetic screening tests may be helpful for assessing early risk of the disease.

- Race. Macular degeneration is more common in whites than it is in other groups, especially after age 75.

- Sex. Women are more likely than men to develop macular degeneration, and because they tend to live longer, women are more likely to experience the effects of severe vision loss from the disease.

- Cigarette smoking. If you smoke, stop. Exposure to cigarette smoke doubles your risk of macular degeneration. Cigarette smoking is the single most preventable cause of macular degeneration.

- Obesity. Being severely overweight increases the chance that early or intermediate macular degeneration will progress to the more severe form of the disease.

- Light-colored eyes. People with light-colored eyes appear to be at greater risk than do those with darker eyes.

- Exposure to sunlight. Although the retina is more sensitive to shorter wavelengths of light, including ultraviolet (UV) light, only a small percentage of ultraviolet light actually reaches the retina. Most ultraviolet light is filtered by the transparent outer surface of your eye (cornea) and the natural crystalline lens in your eye. Some experts believe that long-term exposure to ultraviolet light may increase your risk of developing macular degeneration, but this risk has not been proved and remains controversial.

- Low levels of nutrients. This includes low blood levels of minerals, such as zinc, and of antioxidant vitamins, such as A, C and E. Antioxidants may protect your cells from oxygen damage (oxidation), which may partially be responsible for the effects of aging and for the development of certain diseases such as macular degeneration.

- Cardiovascular diseases. These include high blood pressure, stroke, heart attack and coronary artery disease with chest pain (angina).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests for macular degeneration may include:

- An eye examination. One of the things your eye doctor looks for while examining the inside of your eye is the presence of drusen and mottled pigmentation in the macula. The eye examination includes a simple test of your central vision and may include testing with an Amsler grid. If you have macular degeneration, when you look at the grid some of the straight lines may seem faded, broken or distorted. By noting where the break or distortion occurs — usually on or near the center of the grid — your eye doctor can better determine the location and extent of your macular damage. Regular screening eye examinations can detect early signs of macular degeneration before the disease leads to vision loss.

- Angiography. To evaluate the extent of the damage from macular degeneration, your eye doctor may use fluorescein angiography. In this procedure, fluorescein dye is injected into a vein in your arm and photographs are taken of the back of the eye as the dye passes through blood vessels in your retina and choroid. Your doctor then uses these photographs to detect changes in macular pigmentation or to identify small macular blood vessels. Your doctor may also suggest a similar procedure called indocyanine green angiography. Instead of fluorescein, a dye called indocyanine green is used. This test provides information that complements the findings obtained through fluorescein angiography.

- Optical coherence tomography. This noninvasive imaging test helps identify and display areas of retinal thickening or thinning. Such changes are associated with macular degeneration. This test can also reveal the presence of abnormal fluid in and under the retina or the RPE. It's often used to help monitor the response of the retina to macular degeneration treatments.

References

https://nei.nih.gov/health/maculardegen/armd_facts

http://www.fightingblindness.ie/eye-conditions/age-related-macular-degeneration/

http://www.amd.org/what-is-macular-degeneration/wet-amd/

http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/173/11/1246.long